Murfreesboro has connections to many families who were prominent in the land acquisition and politics of Tennessee in the early days. One of these people was Colonel Hardee Murfree, for whom the city of Murfreesboro is named. Murfree, an aristocratic North Carolina shipping merchant and farmer, had the funds to purchase thousands of acres of land from Revolutionary War veterans who were not interested in moving to property they were given, in what would become Tennessee, for their service in the war. He ended up owning land that would eventually become parts of Rutherford, Davidson and Williamson Counties.

When Colonel Murfree died without a will, his goods and possessions were divided among his living children by probate court in North Carolina where his shipping business was still located. His daughter Sarah “Sallie” Hardy Murfree Maney inherited the land upon which Oaklands is built as part of her inheritance after his death, but it was in fact given to her husband, Dr. James Murfree. At that time women were not allowed to own property.

After several years of probate, the Maneys probably took possession of the land in about 1813. The first structure was a one and a half story, two room brick building completed sometime between 1815 and 1820, as the Maney family is noted as living there in 1820, according census records. The bricks were made by slaves from local clay and fired on the property.

The Building of Oaklands Mansion

The original part of the home eventually became what is now set up in the historic museum as Dr. Maney’s office and the room off the back porch that currently contains a mini museum with photos of what the home looked like before restoration.

As the family wealth grew, so did the structure. A two-story addition was added to the west of the original structure in the 1820s. It was, researchers believe, of a Federalist styling. This part of the home is what is now the dining area and the hall with the curving staircase and a bedroom above.

The third section turned the original part of the home into two stories that provided space upstairs for a nursery, a boy’s bedroom, a girl’s bedroom, and family dining space downstairs near the freestanding summer kitchen that was located outside.

After Sallie Maney passed away in 1857, her daughter-in-law, Rachel Adeline Cannon Maney became mistress. She brought her own wealth to the family, being the daughter of former Tennessee Governor Newton Cannon. After this marriage, Dr. Maney passed much of the management of the estate over to his eldest living son, Lewis and his brother David.

From the fortune that Adeline brought to the marriage and Lewis’ business dealings, the couple were able to add the last section to the front of the home as it is seen now. This section was completed just before the Civil War began and they were only able to enjoy it for a year before fighting broke out. It contains the front parlor and the library downstairs, plus the two bedrooms above the front hall that were used for guests.

Civil War Brought a Change in Maney Fortunes

The Civil War severely damaged the Maney fortune because much of it was tied up in slaves, forcing them to sell the property between the current entrance to the estate and Lytle Street for the creation of Maney’s Addition, a housing development. That move sustained them until after Lewis’ death.

Adeline ended up having to sell Oaklands at public auction to pay her husband’s debts in 1884. She moved into a home in Maney’s Addition where she stayed until her death. Oaklands was purchased by Elizabeth Swope, a wealthy widow from Memphis. Upon her death, it was inherited by her daughter Tempe and son-in-law George Darrow. They were one of Murfreeboro’s first millionaire families. They made a few changes to the house, like putting in a door that opened between the family and public parts of the home. And changed the name to Oak Manor.

Saving Oaklands Mansion from the Wrecking Ball

After the Darrows, the Roberts family moved into the home, and the last family to own the place was the Jettons. In 1954, the city of Murfreesboro purchased the home and surrounding land to build a low-income housing development. They let it sit with plans to tear it down until a group of prominent Murfreesboro women decided to save the house in 1959. In 1974, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

“The original founders of the Oaklands Association wanted to have the house look like it did when the last section was completed,” explained Oaklands Mansion Executive Director James Manning. “They had all of the modernization removed. We have changed that in recent years.” While the home has a deep sense of the early 1860s, post-Civil War pieces have been added to the collection as the museum has received donations from various estates tied to the Maney, Darrow and Roberts families.

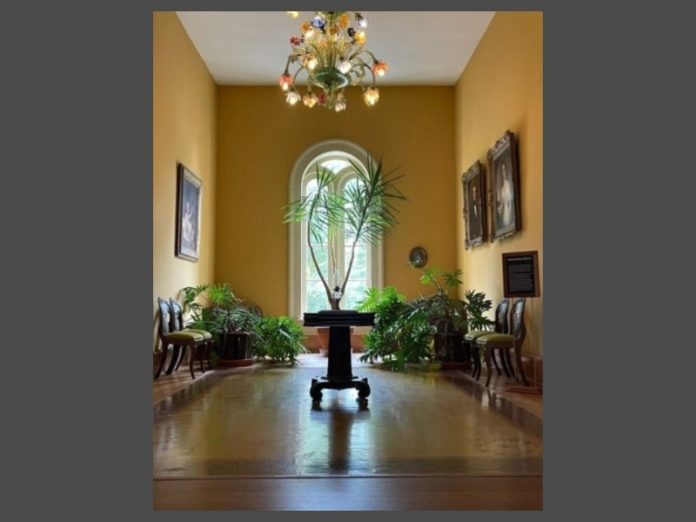

The elegant Italianate mansion had once upon a time been the focal point of a gracious plantation that encompassed 1,500 acres. Now the home is a museum and community gathering place that sits on just a few acres of the original holdings. It is surrounded by a public park. With a meeting space and gift shop in a building that was built in more recent years to look like stables, the museum now celebrates the diversity of Murfreesboro while telling the story of the history of a home that is now a treasured landmark.

Telling Oaklands Story is Ever Changing

Oaklands Museum is far from a static piece of history. Over the years there have been many changes to the home, the grounds and to the story that is told. Much restoration is still being completed. “The mirror in the front parlor is one of our best pieces,” said Manning. “It was just re-gilded in 24 karat gold thanks to a grant from Deana Young and Mike Humnicky.”

The museum has a program to adopt an artifact needing restorations, as well as parts of the architecture. To get the home back to its original grandeur, it will need more pieces restored, wallpaper replaced, doors painted with graining, and much more. For example, there are still doors that were hacked with a hatchet in the 1950s that have not been fully restored. And walls are always cracking and needing repair.

Besides continuing to restore and maintain the mansion, like many museums today, Oaklands is making sure they are telling the full story of the home, so there is a lot of research continuing to be done to tell the stories of all of the families who lived there, including the many slaves who served the plantation.

“We no longer wear period clothing when doing tours because it is painful for people of color,” said Manning. And they have spent an extensive amount of time working with historians and archeologists to ensure they are telling the whole story of the home.

There are no diaries or ledgers from the time of the Maneys, so the research has been slow. However, when the home was saved in 1959, Newton Cannon Maney’s wife was still alive and she shared a lot of stories with the women who saved the home. Stories they saved. And historian Shirley Jones was able to interview Rebecca Jetton, the last person to live in Oaklands in the 1980s, when she was living in the James K. Polk Hotel downtown.

Focus of Museum is Transitioning

The space is transitioning, becoming more of a community event center that also shares the rich history of Oaklands Mansion. The parklands in front of the museum are open to the public from dawn until dusk every day. Those living downtown frequently stop by to say hello to James and his staff. And there are days when as many as five community events will take place on the campus.

“It is important for a site like this to be a community center and not just a house,” noted Manning. “A lot of people have given their time, talents and money to restore and operate this facility, it is part of the community now.”